Your Rotator Cuff Is Not A Cuff

Written by Calvin Sun

There’s no shortage of misconceptions and misinformation in the realm of health, fitness, and nutrition. One of the most common anatomical misconceptions, for both the layperson and the novice coach, is regarding the famed rotator cuff. I often hear complaints about rotator cuff pain despite the pain being in an anatomically implausible location or self-diagnosed rotator cuff “tears” that miraculously heal in a few days. Most people have no idea what or where their rotator cuff is, nor its actual function. In today’s post, I’ll cover the basics of shoulder anatomy and hopefully, clear up some of the misconceptions regarding the rotator cuff.

Many people mistakenly imagine the rotator cuff as a piece of connective tissue that surrounds the shoulder joint. While there is a structure that encapsulates the ball-and-socket joint of the shoulder, it’s actually the articular capsule of the humerus (more commonly referred to as the shoulder capsule). There’s also the labrum which surrounds the shallow shoulder socket known as the glenoid cavity. While these two structures are certainly vital components of the human shoulder, they are not the actual rotator cuff.

So, What Is The Rotator Cuff?

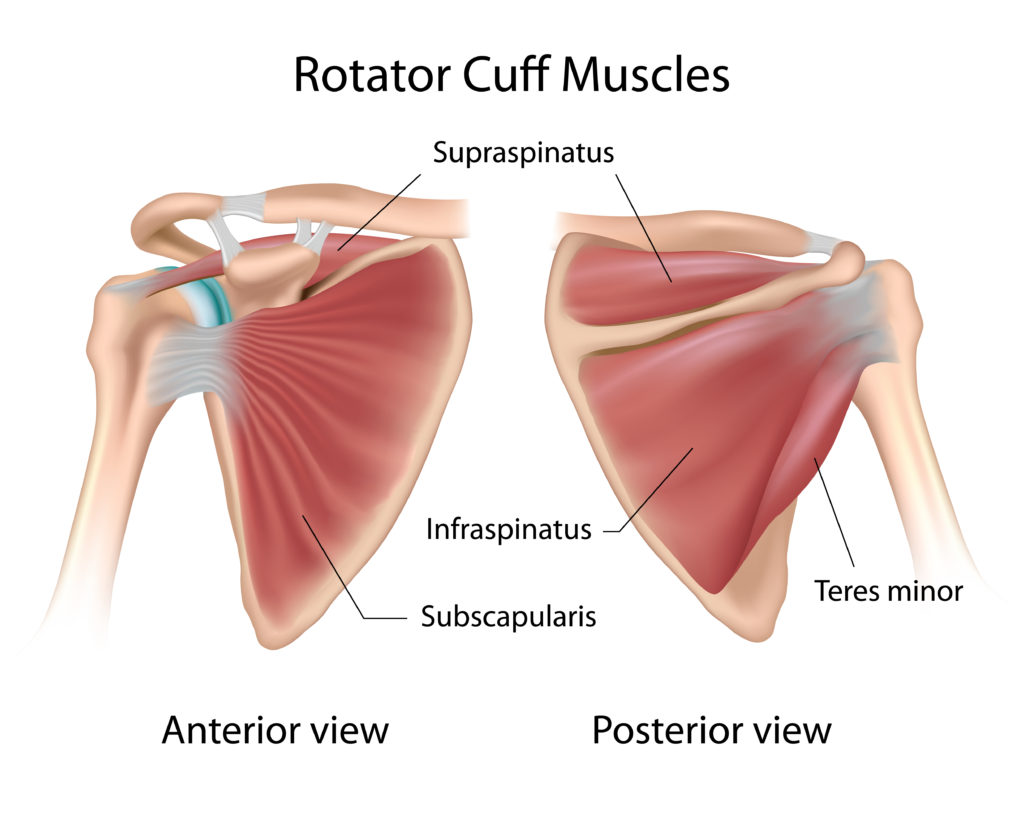

The rotator cuff is actually a group of four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. For the sake of both convenience and clarification, I have listed each of the muscles with their proximal and distal attachments as well as their respective actions.

Supraspinatus

Proximal Attachment: supraspinous fossa of the scapula

Distal Attachment: superior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus

Action: abducts the humerus

Infraspinatus

Proximal Attachment: infraspinous fossa of the scapula

Distal Attachment: posterior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus

Action: externally rotates the humerus

Teres minor

Proximal Attachment: middle half of lateral border of the scapula

Distal Attachment: inferior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus

Action: externally rotates the humerus

Subscapularis

Proximal Attachment: subscapular fossa of the scapula

Distal Attachment: lesser tubercle of the humerus

Action: internally rotates the humerus

Pro Tip: You can easily remember the four muscles of the rotator cuff using the acronym SITS.

What Is The Purpose Of The Rotator Cuff?

The primary function of the rotator cuff is to the stabilize the humeral head on the glenoid cavity. In addition, the rotator cuff creates abduction as well as internal and external rotation of the humerus.

The shoulder utilizes a “ball-and-socket” joint configuration that enables a large and varied range of motion compared to a hinge joint like the elbow or knee. The downside to this increased range of motion is a decrease in stability. In terms of bony structure, the glenoid cavity (the shoulder socket) is quite shallow and small. A deeper socket would create more stability but would also result in a reduced range of motion. Approximately one-third of the head of the humerus (the ball) is covered by the socket. This anatomical arrangement is often likened to a golf ball sitting on a golf tee.

As you can imagine, we don’t want our golf ball falling off our tee. That would be a shoulder dislocation which I assume is not your desired outcome. The rotator cuff muscles all originate on the shoulder blade and insert on the humerus. To simplify, this arrangement essentially pulls the ball into the socket. A strong rotator cuff helps create more stability at the glenohumeral joint which helps prevent subluxations, dislocations, and common overuse injuries of the shoulder. In turn, this allows us to develop stronger pressing and overhead movements which all rely on a stable glenohumeral joint for optimal function.

So, How Do I Strengthen My Rotator Cuff?

A few movements that I like for strengthening the rotator cuff are Cuban presses, external rotations, elevations in the scapular plane, as well as shoulder abductions in the frontal plane. There are numerous variations of these movements which I’ll cover in a future post. In terms of program design, it’s generally optimal to add these movements at the end of a training session or on a day where the shoulder stabilizers will not be needed for larger, compound movements. For example, if you are bench pressing, overhead pressing, or snatching, you can probably imagine that it’s not ideal for you to pre-fatigue the rotator cuff with specific accessory exercises before loading the shoulder with a heavy load.

Be on the lookout for a future post where I’ll provide video demonstrations of my best rotator cuff exercises as well as a free supplemental rotator cuff program you can add into your current training. If you want to learn more about human anatomy, two of my favorite resources are the Atlas of Human Anatomy and The Anatomy Coloring Book.

Do you still have questions about the rotator cuff? Post your questions below in the comments.

Fun Fact: Pulled pork is commonly made from bone-in pork shoulder roast. The bone found in the roast is the shoulder blade of the pig. So, when you have pulled pork, you’re actually eating porcine rotator cuff along with other muscles of the shoulder region.

Also Check Out…

fun fact im gay

malte is gay